What a Mess

Chaos and Creativity

The idea has been controversial from the start, for many reasons, but it does get some empirical support from psychological science. A growing body of research suggests that the human mind does like order and structure and rules. Indeed, cleanliness and tidiness have been shown to promote legal and moral action, while a messy environment appears to do the opposite.

But this idea may be a little too tidy, and some scientists are beginning to challenge it. If it were that simple, how should we explain the fact that order and disorder are both common states? Why hasn’t the human yearning for order, over the millennia, triumphed over messiness in society?

This was the point of departure for psychological scientist Kathleen Vohs and her colleagues at the University of Minnesota. Vohs wondered if perhaps environmental order and disorder are both functional, activating different, but equally valuable, mindsets. Maybe what we disparage as messiness—maybe this physical state contributes to a varied world, and perhaps it’s variety that’s most important in shaping human thinking and action. She and her colleagues ran a couple experiments to test this provocative idea.

Vohs wanted first off to explore the effects of order and disorder on socially desirable behaviors, so in the first experiment she looked at healthy eating and charitable giving. These are both things that, by common agreement, are good. She recruited volunteers and, unknown to them, had some work in a tidy room and the others in a messy space. They filled out questionnaires that weren’t really relevant to the study, and afterward were given the opportunity to donate privately to charity—specifically, to help pay for toys and books that would be given to children. Then, as they were departing, they were offered the choice of an apple or chocolate.

The results were unambiguous. Those who had been working in an orderly workspace were more generous. Not only were they more likely to donate anything to the kids, collectively they donated more than twice as much money to the charity. They were also more likely to make the healthy food choice.

Okay, so this merely reinforces what’s been known—that an orderly environment leads to desirable and good action. But is there a downside to this mindset? In a second study, Vohs took a different tack and explored contexts in which messiness might lead to a socially desirable outcome. She figured that, since order promotes conventional values, maybe disorder promotes breaking with convention—the essence of creativity.

To study this possibility, she again had volunteers work in either a neat or a messy room. Volunteers completed the same kinds of filler work as before, followed by common a test of creativity. Specifically, they were told to come up with as many as ten new uses for ping pong balls, and their answers were scored by independent judges.

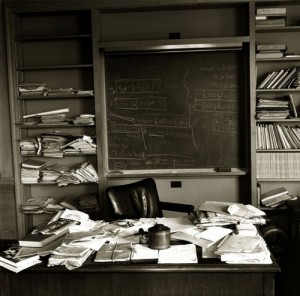

Taken together, these findings challenge the well-entrenched view of order and disorder as too simplistic. It’s misleading to conclude that messiness promotes wild, harmful and morally suspect behavior, or that order leads to honesty and goodness. A more nuanced view would add that disorder also inspires breaking from tradition, which can lead to fresh insight, and that order is linked to playing it safe. Vohs concludes with the example of Albert Einstein, who famously quipped: “If a cluttered desk is a sign of a cluttered mind, of what, then, is an empty desk a sign?”

Wray Herbert

February 20, 2013

︎